A recent Ninth Circuit decision, Chabolla v. ClassPass, Inc., underscores critical considerations for retailers with online Terms of Service / Use agreements, particularly regarding arbitration provisions and related consumer privacy litigation risks. The plaintiff, Katherine Chabolla, alleged that ClassPass violated California’s Automatic Renewal Law, Unfair Competition Law, and Consumers Legal Remedies Act by resuming auto-renewal charges after a pandemic-related pause. ClassPass argued that Chabolla had agreed to arbitrate any claims against it through her interaction with its website.

The central dispute concerned whether Chabolla had effectively agreed to the Terms of Use of Class Pass website, and specifically its arbitration provision, through a “sign-in wrap” agreement. Unlike traditional “clickwrap” agreements that require express user consent via a checkbox or button clearly indicating assent to terms, sign-in wrap agreements provide a link to terms of use and indicates that some action may bind the user—e.g., “I agree to the Terms of Use” followed by a “Sign up” button—but do not expressly require that the user view those terms.

The court found ClassPass’s website design insufficiently clear, determining that the plaintiff did not unambiguously manifest her consent to the arbitration clause, owing to supposedly ambiguous placement and phrasing of terms across multiple screens. Specifically, ClassPass used three different screens for the sign-up process.

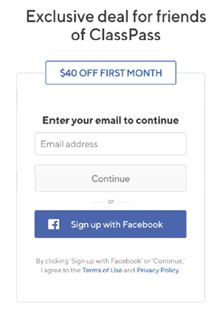

The first screen disclosed the “By clicking ‘Sign up with Facebook’ or ‘Continue,’ I agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy.”

Even though the terms “Terms of Use” and “Privacy Policy” appeared in a different color (blue, signifying hyperlinks), the panel still found that this disclosure did not provide specific notice. The panel concluded that the language was in a smaller font and not sufficiently visible because it was (supposedly) on the “periphery” of the sign-up box; thus, held the panel, a “reasonable user” (supposedly) would not think to look down to see the terms. It reached that conclusion even though the entire sign-up box, including the assent disclosure, appeared to consumers without any scrolling needed.

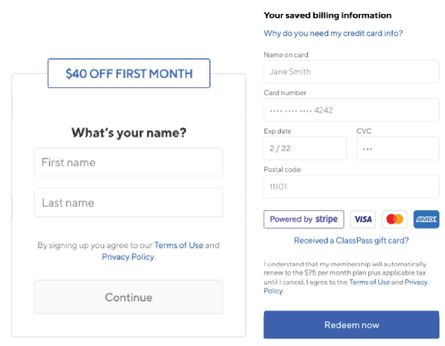

The second screen stated that “[b]y signing up you agree to our Terms of Use and Privacy Policy,” and the third screen contained a similar disclosure.

But the panel found that the action buttons available, “Continue” and “Redeem now,” respectively, were somehow ambiguous and a reasonable user supposedly would not understand clicking on them as a manifestation of assent.

Notably, the panel’s decision was 2-1. The dissent strongly argued that the plaintiff had sufficiently conspicuous notice of the terms and had unambiguously manifested her assent. The dissent emphasized that the terms were linked in clear, legible text near action buttons the plaintiff had to click multiple times to proceed through the subscription process. It argued that each screen individually and collectively provided adequate notice, and that the majority’s approach would unnecessarily disrupt established practices in online consumer agreements, encouraging businesses to revert exclusively to more explicit “clickwrap” or “scrollwrap” models.

The dissent ends by warning that the panel’s decision shows that courts “will examine all internet contracts with the strictest scrutiny and that minor differences between websites will yield opposite results.” This is absolutely true, and the implications of the ClassPass decision are significant for all retailers with an online presence. This ruling serves as a potent reminder that compliance with web design standards may not be enough to enforce arbitration clauses, especially on consumer-facing platforms where transparency and clarity are increasingly scrutinized. It also highlights the Ninth Circuit’s reluctance to enforce arbitration agreements without express, unambiguous user consent, and the Circuit’s tendency to treat the “reasonable” person as some naïve internet novitiate from a long-passed era, rather than recognize the realities of e-commerce and the average person’s understanding in 2025. Websites must clearly inform users that their actions signify agreement to terms and conditions, particularly arbitration clauses.

Retailers should immediately review their web design practices and consult with their IT and legal teams to ensure their online agreement processes are sufficiently explicit to withstand judicial scrutiny. Clear, direct language next to actionable buttons remains critical. Companies must adapt swiftly to this clarified legal landscape to mitigate litigation risks and ensure robust defenses in potential consumer-privacy and related class-action disputes.

For more information on this topic, contact David M. Krueger at dkrueger@beneschlaw.com or 216.363.4683.

Michael Meuti is Chair of Benesch's Appellate Practice Group. He can be reached at mmeuti@beneschlaw.com or 216.363.6246.

Meegan Brooks is a Partner of Benesch's Retail & E-Commerce Practice Group. She can be reached at mbrooks@beneschlaw.com or 628.600.2232.